Whittlesey is at the heart of a growing public health debate as residents and officials grapple with the cumulative impacts of industrial activity at Saxon Pit. The latest submission from Cambridgeshire County Council’s Public Health team, led by Dr. Sarah Dougan and Dallas Owen, paints a picture of a town under strain—physically, mentally, and environmentally.

Residents living near Saxon Pit have voiced persistent concerns about noise, dust, and odour, with many reporting a decline in their quality of life and growing anxiety about the health of their families.

“We are breathing in this dust and concerned for our health and that of our children and grandchildren,” one Whittlesey resident wrote in response to the Environmental Permit variation for Johnsons Aggregates and Recycling Limited (JARL) in November 2025.

Despite these testimonies, the applicant’s Health Impact Assessment (HIA) concluded that health impacts are minimal and that no complaints had been received a finding that public health officials and residents alike find “surprising” and “concerning.”

The Saxon Pit site is a complex mosaic of industrial operators, each contributing to the environmental burden.

Residents on Peterborough Road, Snoots Road, and Priors Road report daily exposure to dust, noise, and odour, with visible deposits on homes and vehicles. The situation is exacerbated by heavy goods vehicle (HGV) traffic, which blankets the A605 in dust despite regular road-sweeping.

For many Whittlesey residents, environmental disturbance is not a new phenomenon.

Complaints about dust, noise, and odour have intensified in recent years, with some residents reporting that the situation has worsened since the expansion of operations at Saxon Pit.

The ongoing buttressing work by East Midlands Waste, originally expected to last a few years, remains incomplete, prolonging the community’s exposure to industrial emissions.

Public Health’s strong view is that Whittlesey may have reached—or is close to reaching—the “tipping point” where cumulative impacts become unacceptable. It suggests the need for health impact assessments to systematically capture and address community health concerns.

The debate over Saxon Pit, Whittlesey, is no longer simply about planning applications or industrial regulation. It is about health: the air we breathe, the noise that disrupts sleep and the dust that settles on homes and gardens.

The newly published Cambridgeshire County Council Public Health report into operations at Saxon Pit has attempted to answer a central question repeatedly raised by residents: are the activities on the site harming public health?

The report offers a mixture of reassurance and caution. While it concludes that there are “no identified risks to public health” from certain exposure pathways based on existing data, it also acknowledges significant limitations in evidence and calls for further work to understand cumulative and mental health impacts.

For campaigners in the Whittlesey residents’ group Saxongate, those limitations are not a minor footnote but the heart of the issue. As they see it, the report confirms what residents have long argued: that health concerns have not yet been fully addressed.

Local councillor Chris Boden said the concerns of residents had been raised over many years and led last summer to a public health consultant convening an incident management team to investigate whether the site posed risks to human health.

Councillor Boden stressed that the report should be seen as a significant turning point rather than a clean bill of health.

He highlighted that Public Health officials are not satisfied that dust and particulate matter from Saxon Pit have been adequately measured or assessed. As a result, he welcomed commitments within the report to improve monitoring, carry out further research and adopt a more resident-focused approach.

He also described the recommendation to refuse Johnsons’ expansion plans as an important development, saying that while the broader fight against pollution in Whittlesey is ongoing, the report represents a meaningful victory for local residents.

The issue has also attracted attention from Whittlesey’s MP, Steve Barclay, a former Environment Secretary. Barclay said he has repeatedly raised residents’ concerns with the County Council, echoing issues highlighted by Saxongate, including water pollution, noise, odour and dust.

Commenting on the report’s findings, Barclay noted that it identified elevated levels of heavy metals in the water, but because the water is not classified as drinking water, this was not deemed a public health risk. On issues such as noise, odour and dust, he said the Director of Public Health had acknowledged that further monitoring is required and committed to additional work.

He warned that granting permits for further activity would be a mistake, particularly given that resident concerns remain under investigation.

What the public health report says

The public health risk assessment was commissioned by Cambridgeshire County Council in response to “public concerns about the site, off Peterborough Road”.

It examined potential risks to human health from emissions to air, land and water from current operations at Saxon Pit, with input from multiple agencies including the UK Health Security Agency, Fenland District Council Environmental Health and the Environment Agency.

According to the County Council’s press statement, the report “makes several reassurances and suggests further evidence would be useful to fully assess other aspects”.

Specifically, it finds that there are “no identified risks to public health” from water in King’s Dyke being used for livestock, from land gas emissions, or from air quality at Hallcroft Road, where monitoring data shows compliance with national air quality objectives.

Sally Cartwright, Director of Public Health at Cambridgeshire County Council, said: “We are pleased to have carried out this work with our partners, which brings together all the available relevant data on the potential health impacts of these operations in the community.”

She added that the assessment shows “the regulatory arrangements for the site with multiple activities is complex, and that understanding the combined effects on health can be challenging”.

That complexity is reflected in the number of operators on and around the site.

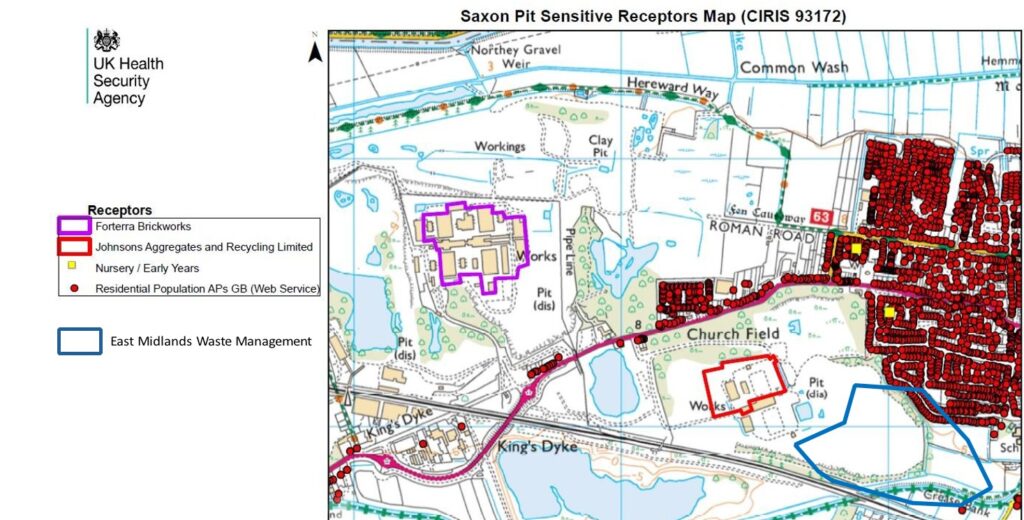

As the report states, three businesses operate on or near Saxon Pit: Johnsons Aggregate Recycling, which treats incinerator bottom ash; Forterra, which manufactures house bricks; and East Midlands Waste Management, which imports waste to stabilise the pit face and has permission to recycle metal.

All emissions are regulated through Environment Agency permits, and the report says, “the site as a whole is operating at an expected level of permit compliance”.

Yet the same report also highlights gaps. It states that further evidence would be beneficial to assess air quality at the Saxon Pit boundary, whether there are ongoing noise or odour issues, and “any cumulative health impacts, including on mental health”.

Noise, dust and daily life

For Whittlesey residents living closest to the site, those gaps are not abstract. Noise remains the most frequently reported issue.

According to the public health documentation, noise has been the subject of ongoing investigations by Fenland District Council and the Environment Agency. Residents have described noise as persistent and disruptive, affecting daily life and wellbeing.

Dust is another major concern. The report notes that elevated levels of dust have been recorded on-site, but that it is “not possible to attribute this to specific sources or to assess public health risks based solely on deposition data”.

Monitoring, it says, is focused within the site boundary and uses workplace exposure limits rather than public health standards.

The public health report accepts that air quality monitoring has limitations.

Monitoring data from Hallcroft Road indicates compliance with standards for PM10 and PM2.5 particulate matter, but the report acknowledges that air quality is not monitored at the Saxon Pit boundary and that there have been periods of equipment downtime. As a result, “there is a gap in understanding potential exposure for residents closest to the site”.

This gap is significant because it goes to the core of residents’ health concerns.

Without boundary monitoring or analysis of dust composition, it remains unclear what levels of exposure people living near the site are experiencing, or what the long-term health implications might be.

Mental health and cumulative impacts

Perhaps the most striking area where the report acknowledges uncertainty is mental health. The documentation states that cumulative impacts on health and wellbeing, including mental health, “are not fully understood and require further assessment”.

Residents report that their health and wellbeing are affected by noise, odour and dust, and by concerns about the processing of incinerator bottom ash, which is perceived as hazardous. The report recognises that the regulatory system is “complex and fragmented”, contributing to “a loss of public confidence and trust”.

Sally Cartwright addressed this directly, saying: “The cumulative impacts on health and wellbeing need to be better understood and assessed, and we’re proposing further work to address that.”

For many residents, the mental health burden comes not just from environmental exposure but from years of uncertainty and perceived inaction. The stress of repeatedly raising concerns, navigating complex regulatory systems and waiting for definitive answers can itself become a health issue.

Saxongate’s response highlights this dimension.

They state that the report “does not identify any current public health risks based on that specific scope and evidence, but it also makes clear that its conclusions are constrained by both the data available and what was within scope”.

In other words, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

Planning, expansion and unresolved questions

The timing of the public health report is particularly significant because it coincides with a planning application by Johnsons Aggregates and Recycling Ltd seeking to substantially increase the amount of incinerator bottom ash processed at the site and to introduce outdoor IBA crushing.

On the same day the health report was published, Cambridgeshire County Council Public Health submitted an eleven-page objection to that planning application. That objection, Saxongate notes, is publicly available on the planning portal.

This juxtaposition has not been lost on residents. On one hand, a public health report offers reassurance based on limited data; on the other, the same public health team raises objections to a proposed expansion, citing concerns that health and wellbeing may not be adequately protected.

Within the objection and related commentary, public health officials stress the importance of considering cumulative impacts and the potential for Whittlesey to be approaching a “tipping point” where combined industrial activities become unacceptable for community health and wellbeing.

Are health concerns being addressed?

So, are the health concerns of Whittlesey residents being addressed? The answer depends largely on perspective.

From the County Council’s standpoint, the publication of the report itself is evidence of action.

The assessment was instigated in response to public concern, involved multiple agencies, and resulted in clear recommendations. These include quarterly meetings between regulators and residents, a cumulative community health impact assessment, enhanced water monitoring, development of an air quality monitoring strategy, and exploration of stronger waste and health policies.

“We’d like to involve the community as we move forward,” Sally Cartwright said, adding that plans include “quarterly regulator meetings with residents and to establish a new larger group, including community representatives, to oversee the delivery and implementation of the recommendations arising from this assessment”.

From Saxongate’s perspective, these steps are welcome but overdue, and they underline rather than resolve the problem.

The group notes that air quality is not monitored at the site boundary, that dust composition has not been assessed, and that further evidence is needed to understand “dust, noise, odour and cumulative health impacts, including mental health”.

They emphasise that the report’s conclusions “need to be read alongside the limitations it sets out and the actions it recommends”.

Until those actions are completed and new evidence gathered, many residents feel their health concerns remain unaddressed in practical terms.